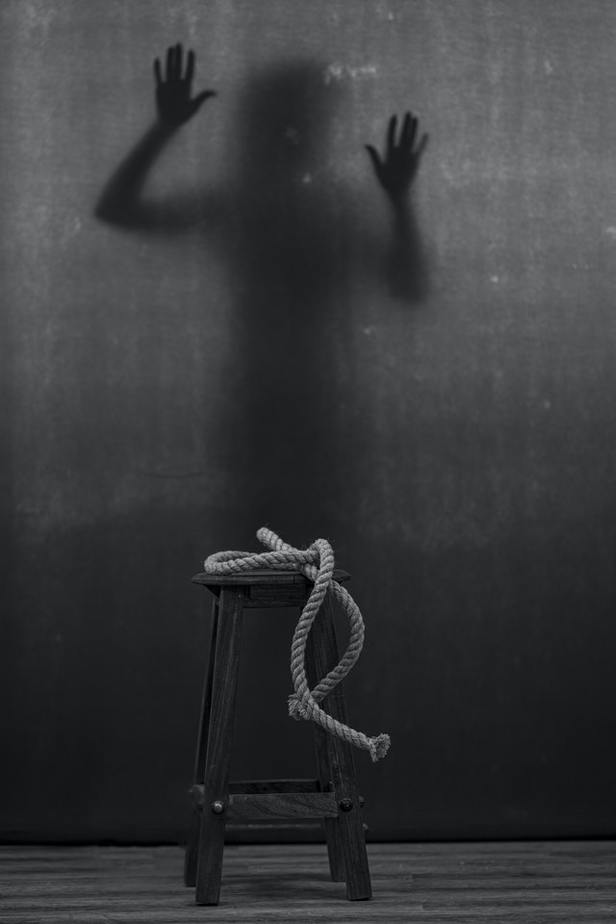

finding the monsters hidden in your story

You know the drill by now. If you don’t, check out the last 2 posts!

Whether you create from a meticulous outline or follow where the fancy takes you, your first draft could always use some work. One of the most important stages of sprucing up that manuscript is cutting unnecessary verbiage.

Remember, space is limited: anything that isn’t contributing is hindering.

We all know that, of course, but monsters are sneaky. They hide in plain view. I’m here with the monster-spotting goggles on, helping you hunt them down and <backspace> right over them.

Episode 3: The narrative gets possessed by the narrator

nightmare on fatuous-rhetorical-question street

We all know how this goes. We’re all guilty of it. Your protag is facing a startling reversal or a puzzling new situation and you express this by creating a string of questions: What were they going to do? How had this happened? What had they done to deserve this?!

In essence, you’ve mistaken your own stream of consciousness — the writer trying to come to grips with the plot twist you’ve introduced — for the narrative. Friend, I’m here to tell you: the readers don’t care what you’re thinking. It’s the characters they’re interested in.

I attended a virtual writing conference this spring where a panel of literary agents listened to a moderator read the first page of real people’s real manuscripts, and raise their hands when — had it been a submission — they would have stopped reading.

There was a lot of variety; the agents had different specialties and different tastes. Then we come to this really compelling YA spec fic. He’s been reading for a while, have to be getting close to the end of the page, no hands up: everyone likes this story. I know I did.

Then we hit a paragraph composed entirely of questions. BOOM. Like it was choreographed, every single hand goes up.

You know me: I’m rarely a fan of rules without exceptions. I’m not saying you can’t ever use a question outside dialogue. Just ask yourself if it’s the best way to convey this information.

Instead of: What was he going to do about these weevils? Try: He wondered what he was going to do about these weevils. You’ve introduced action into the sentence. A question makes it seem as if the reader is responsible; a statement puts agency back where it belongs, in the hands of your characters.

Congratulations! Your hero isn’t hiding in a closet, they’re strapping on the weapons and taking charge.

Next week, Count Vampire is going to monologue on something no one gives a damn about.

Comments are closed